The Sublime Nature of Window Seats

A window seat in an airliner can become a portal into a different view of the world, leaving behind the every day life of sights and sounds as a journey unfolds across the sky, filled with reflection.

You are floating above the earth, no real sense of speed, or time, but the landscapes are slowly passing beneath. You feel disconnected from the physical world, but filled with the sense of sky and space around you. Maybe a pilot lets you know that they are diverting around a massive cumulonimbus structure over Colorado, and you just gaze out the window at the monstrosity to the port side of your craft, blackened storm cells, dark billowing cloud structures, lightning bolts illuminate the thunder cells in sudden bursts of electrical flashes inside the brooding formation. But the air is smooth. You don’t really feel any sense of drama unfolding.

It’s a window seat. A panoramic view of the earth’s surface. You understand why pilots love to fly. Why astronauts and cosmonauts venture even farther out, into the stratosphere, riding the outer limits of technology.

I’ve always booked window seats on planes. For more than forty years now.

I love the sensation of looking down on the earth, seeing the snow capped mountains, the rivers, the cities, the night lights, the cloud formations, a full moon reflecting across the Great Plains. There is a timelessness about it, escaping the confines and limitations of life on the ground. Contemplations abound when you are higher than even the tallest mountain ranges in the world.

When I flew between San Francisco and New York for years, I had memorized the landscape coast to coast. I could look out the window and know where I was. Flying west beyond New Jersey, I would look for the Susquehanna River, lined with uneven and organic shaped farm fields of Pennsylvania that spilled into the river valley. Then, passing over Pittsburgh where the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers meet to form the Ohio River.

And as we continued farther west the farm fields would begin to take on a larger form in Ohio and Indiana, more geometric in shape. Chicago appeared massive, especially at night as the lights grew more and more intense toward the city center, then were sheered off by the dark waters of Lake Michigan to the east.

Iowa was always a wonder, especially at night. You could see the endless 640 acre sections of land, laid out in giant squares, defined by farm lights. I remembered a night when I was driving out near Nevada, Iowa, after visiting a farmer and riding in his combine until midnight harvesting soybeans, talking about the farm industry, families, and our personal lives.

After leaving the farm, I stopped and got out of my car. The night sky had exploded in star studded illumination of the Milky Way. There was no urban light pollution out there in the Iowa countryside. That moment seemed as surreal as looking 30,000 feet down from the plane seeing the farm lights in the night.

There is also an illusionary sense being up in the air at night with the stars out and the rural lights of Nebraska fading into the distance. They weren’t as geometrically spaced as the Iowa fields, they were more random, like the stars. It was as if the plane was in an enormous space, where lights on the ground appeared as stars and there was no longer a horizon line, just dark space, and stars all around the plane.

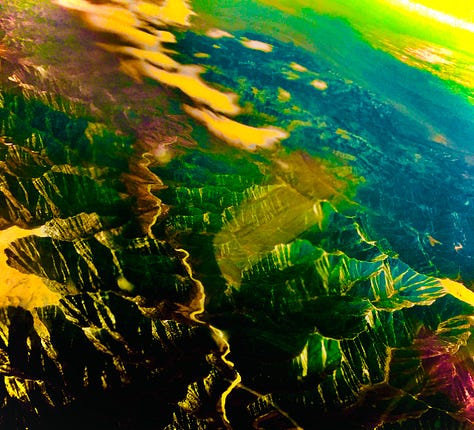

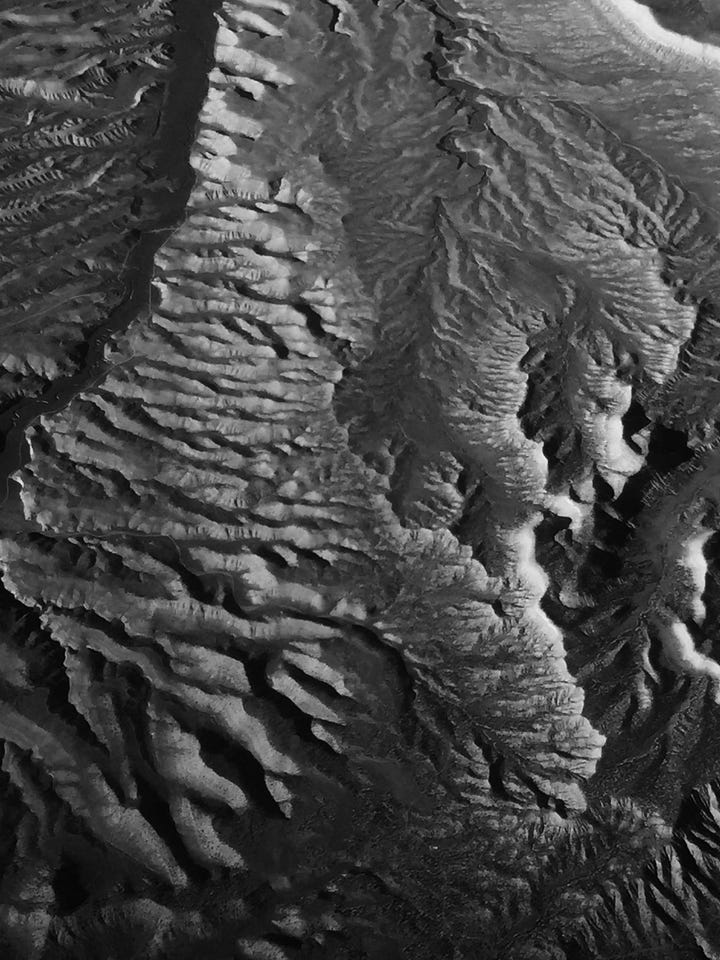

Sometimes you can spot a place on the earth’s surface, even a very remote spot, that you had actually stood. On a flight from Texas to Los Angeles, I peered out the starboard window to the Grand Canyon, then Havasupai lands, on the western edge of the canyon, and a remote, rocky peninsula that jutted out into the canyon. Not a park, just a Havasupai wilderness road that vaguely ended at the edge of a cliff.

I’d driven out there five times in my life, in Jeeps, until the road ended among the scrabble of rocks at the precipice of the Western Grand Canyon. As I looked out the plane window, I could see the peninsula, and exactly where I’d stood. I’d never seen another person out there on any of my journeys. And there, it could be so silent, that the sound of a bird’s wing, dipping in flight to make a turn, could startle you. It was a place where time stood still, like looking out the plane window that day at the sprawling red rock lands of the southwest, slowly passing beneath.

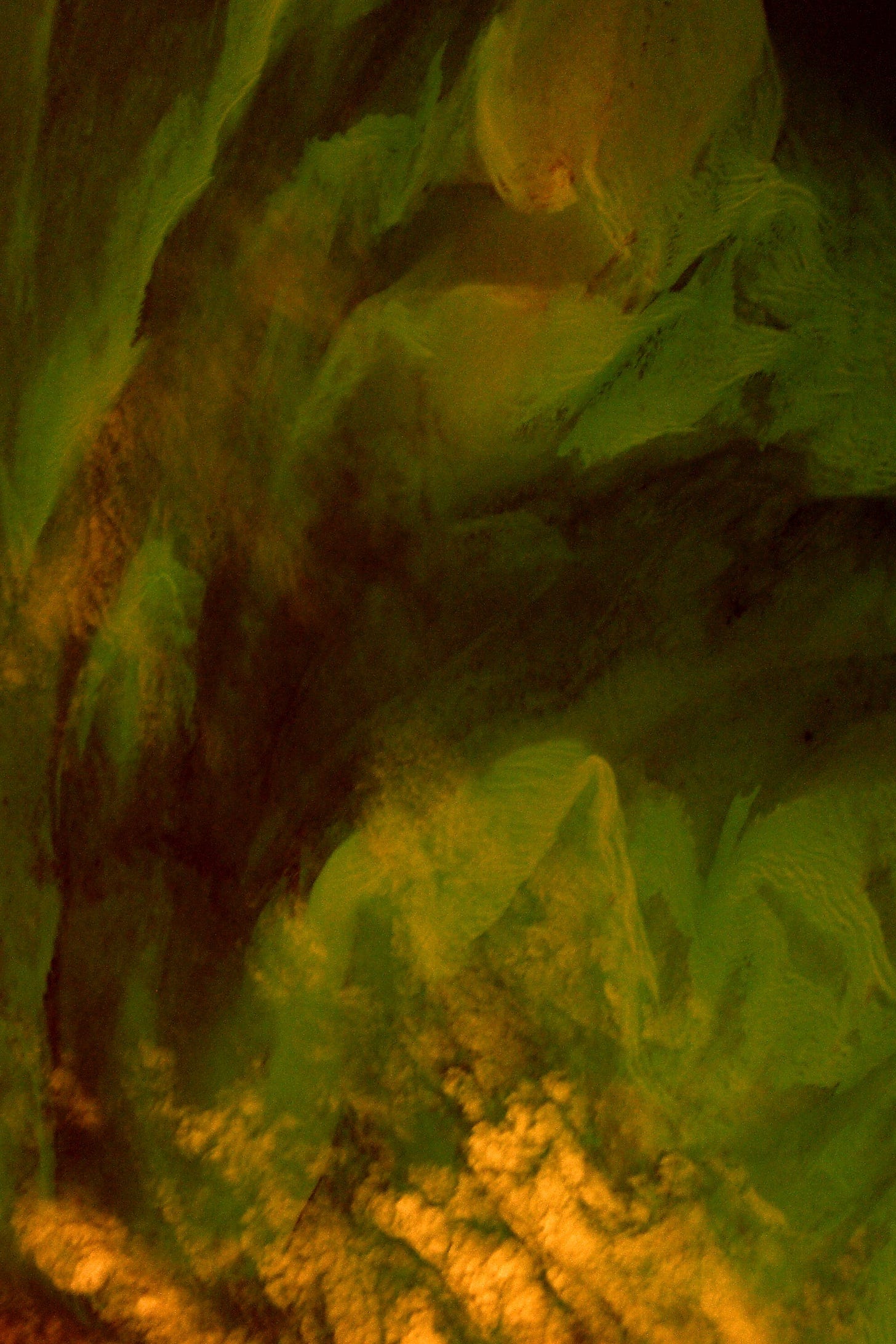

At times, the plane window is a picture frame for art. Maybe even a Zen way of seeing the world. You measure your breathing as you study the awesome landscape below, clouds above, sometimes appearing as sculptures, compositions, with earthly colors. You can later re-mix those colors and shadows within the digital photograph. Over the Caribbean, a green and gold ghost swirls above the islands. A Kandinsky like oil canvas emerges over the Salt Flats of Utah. The clouds portray ghostly shapes.

The window seat can be scary as well. Like over Southern Russia, on a blue sky day, over the Caucasus Range, when the plane shook violently. There were faces outside our plane window, peering back at us from the windows of a Yak airliner, very near to our Tupalov plane. We were so close. The turbulence was caused by our plane flying directly across the jet engine wake of the Yak.

There was a time when you could listen to the pilots and air traffic controllers communicating with each other on their radios. It was like a private network of people up in the sky, chatting away. United Airlines Channel Nine. I’d put on the head set, sit back, and look out the window, listening to pilot dialogues. The air traffic controllers in different regions would hand off transmissions, saying “Good day.” The pilots talked about weather. Which elevation had the smoothest air. How the ride was going.

Once, flying into Newark Airport in a thunderstorm at night, as I looked out the window, a lightning bolt hit our port wing, causing an unstable movement of the plane. I was alarmed. But over the headphones on channel nine, I heard our United pilot report the incident in the most casual of voices to the controller - ‘United Flight xxx, lightning strike port side, tower, over.’ Tower: ‘Ok United, we’ll let flights know.’

Just another night in the sky.

At times, I realize my obsession with windows in planes is starting to run against the grain of today’s flyers. When I walk back through the plane isles, most of the windows are shut. People are watching films, spread sheets, emails, text messages, playing video games, or sleeping. On occasion somebody will ask me to shut my window so they can better view their computer screen. I politely decline.

Then there was the most recent flight in my million plus miles in the skies. A flight from Iceland to Oregon in late November 2024. Port side window. Lifting off from Keflavik Airport into a sunset. The sunset would last for eight hours, over Greenland, Nunavut, Alberta, and into the Pacific Northwest. It was the longest continual sunset that I’d ever experienced. Certainly the time of season, position of the earth and sun, and our flight pattern, all played a part in such a sustained visual.

Only to be viewed from a window seat.

jhg - 2024

All photos are by my mobile phone, except the night shot in Tokyo by Yasuo Osakabe

For information about my books: https://moonstonepublishing.com/

Further reading: Skyfaring - A Journey With a Pilot - by Mark Vanhoenacker