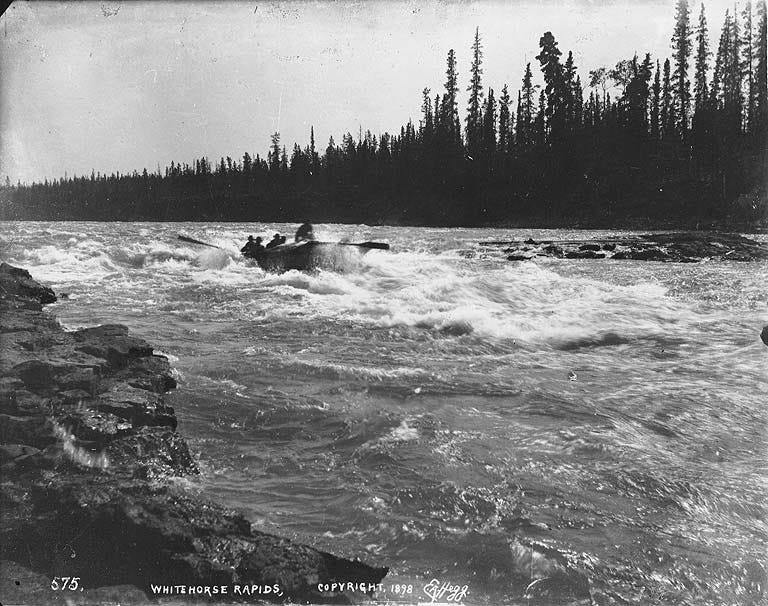

Running the White Horse Rapids in 1894

Running white water is a trendy and risky recreational adventure these days, but one hundred and thirty one years ago in the Canadian wilderness, it was do or die with few rescue options available.

The Yukon was a wild place in 1894. My grandfather, Humboldt LeRoy Gates, was twenty-years-old when he trekked two thousand pounds of gear up over Chilkoot Pass and headed down the Yukon River toward the Klondike. Gold fever did that to people, made them do crazy things. Ripped them out of their everyday life. He’d quit college in his first year. He had no idea what was ahead, other than the trail, the river, and the scent of gold.

That first winter he camped on Marsh Lake near the Yukon River, preparing for the most dangerous leg of the journey through the White Horse Rapids. During the weeks of preparation at Marsh Lake, he lived in a tent. He hunted in the wilderness for food and cooked over open fires. He was a dead shot. He worked every day, building a large river skiff by hand. It was tedious, using a hatchet and saw. A hammer. Some boards he was able to purchase from a small mill that had been setup near Marsh Lake to supply planks to gold miners.

There were few rules in 1894. It was still two years before the actual Klondike Gold Rush would kick off. People heading for the Klondike at that point were speculators and dreamers. Once the actual Gold Rush exploded onto the scene in 1896, then things would get really crazy.

When the 1894 spring thaw came, Humboldt pushed his hand-built, wooden boat out into the broad, heavy flow of the Yukon River and headed down toward the rapids. His father, LeRoy, had taught him how to use oars and position the boat to run through rapids, without broaching or flipping. LeRoy had been a river guide and log boom pilot on the Wisconsin River. They’d practiced in the rivers of Humboldt County, California, where my grandfather was from. His father showing him the ways of wild rivers.

As his boat tossed and turned, Humboldt entered the upper area of the canyon. This stretch of water would end up etched into his mind for most of his life. People had died here. He almost died there in a later incident.

That first trip through White Horse Rapids was a frightful experience, riding those five-foot rolling peaks of white water, pounding over submerged rocks that kicked up waves, spray and turbulence, sending a backwash that was unpredictable, twisting the boat sideways at times. Humboldt pulled manically on the oars to avoid slamming into the basalt rock walls that the current swept hard against at bends in the river. He fought with the oars all the way through the rapids, negotiating every obstacle. Luck would be with him on that first run through the canyon. He made it through safely.

But that wouldn’t always be the case.

Three Years Later at Miles Canyon and White Horse Rapids

Over the next three years, Humboldt became one of the few Klondikers to strike it rich. His brother, two sisters, and step-father would join him to help manage more than a dozen mines near Dawson City. As his mines became profitable, Humboldt attracted investors from Chicago, who kicked in money to purchase a dozen mining plants and transport them to his claims in the Yukon.

Buying the mining equipment was the easy part. Getting it to the Yukon was daunting. They had to get the equipment through the White Horse Rapids.

Humboldt had never forgotten his first trip through the turbulent waters. This time he’d have twelve mining plants on three flat bottomed scows. The machinery was loaded onto the scows at Bennett Lake, just above Marsh Lake. They shoved off for the Yukon River toward Dawson City. He was certainly feeling adrenaline build up as he entered the rocky escarpments of Miles Canyon, just above White Horse Rapids.

He paid two river pilots to guide two of the scows and he piloted the third boat.

He went first, with four mining plants and five men aboard. They entered Miles Canyon. The barge-like craft was hard to handle. The forward sweep oar that Humboldt fought with, snapped off in his hands. He lost control. The vessel careened down the rapids into one of the towering basalt walls, overturning. The scow sank in no time at all.

Humboldt and his two crewmen were swept through the canyon. Eight-thousand dollars worth of mining equipment sank beneath the rapids. The men crawled out of the river at a low bank. One of Humboldt’s friends and crewman, Isaac Robinson, drowned that day.

It would get worse.

Humboldt joined the two river pilots and score of crewmen on the other two scows. They re-grouped and shoved off again, renewing their descent of the Yukon, heading into the roughest stretch of water, the last thirty miles through White Horse Rapids, before Hootalinqua River.

They made it twenty-eight miles. Then a second disaster struck.

Caught in the powerful spring thaw runoff of the Yukon, both scows were swept into a massive rock that protruded up through the rolling white water. The weight of the mining machines on board the flat-bottomed vessels was proving too much to maintain steerage. Sheer momentum took over. One after the other, both scows hit rock, broke up, and sank.

Humboldt and his crewmen were again cast into the swirling icy waters and swept down river hundreds of yards, swimming for all they were worth, trying to reach the banks of the Yukon.

They all made it in the end. Soaked, beat up, but in good spirits, having survived the ordeal, though they were sorry about Isaac Robinson.

They’d lost all three scows and all the mining equipment that day. There were no means of recovery or salvage in the heavy rapids. The entire twenty-five-thousand-dollar investment for the twelve mining machines had vanished.

In today’s worth, that would be a million dollar loss of equipment. It was a big setback for their Klondike mines that spring, but they would recover and prosper over the next four years. It would also be the first and the last time my grandfather would ever try to deliver mining equipment through the White Horse Rapids.

San Francisco - 1908

Nine years after losing the three scows in the White Horse Rapids, Humboldt Gates sat with ‘Swiftwater Bill’ Gates in San Francisco’s St. Francis Hotel lobby, reminiscing about their times in the Klondike. A San Francisco Chronicle reporter had joined them. Swiftwater Bill was a colorful, well known character from the Klondike. He and my grandfather knew each other from those days.

“Hey Bill,” Humboldt asked, “How’d they ever come to call you Swiftwater?”

“Well it happened between White Horse Rapids and the pass (Chilkoot),” Swiftwater said, “Three fellows were stuck out in the river, about 400 men onshore. Nobody offered to go out and save them. I took a chance. I got a rope to ‘em and we got ashore all right. Then some fellow started yelling - ‘Three cheers for Swiftwater Bill!’ They rushed and packed me around on their shoulders. After that, I was always Swiftwater Bill.”

“Well,” Humboldt responded, reflecting on his ordeal in the White Horse Rapids, “I went through those same rapids myself, Bill, only I went under ‘em - lost a whole outfit, a lot of machinery, and another man. But you’ve always been luckier than I have been.”

“Oh I don’t know”, Swiftwater responded, gazing out the St. Francis Hotel windows, “I’ve been married four to five times.”

jhg - 2025

Author’s note - this is an edited excerpt from a larger story that I am currently working on in a new book.