Riding Iowa's Legendary Ragbrai

The largest bike rally in America. You're standing with 10,000 bike riders at the Missouri River, about to launch into an epic, week long, 450 mile ride across Iowa, to the Mississippi River!

My biggest rookie mistake riding Ragbrai the first time in 2014, was to pace myself hard for eighty miles on day one and end up in camp more than two hours ahead of the first veteran rider in our group of 15 bicyclists. I even beat the team bus there. The more seasoned riders rolled in all afternoon, with stories to tell about the people they met along the way, exhibits they explored in the tiny rural communities, home made food they sampled, different microbrews they downed, and the open grills and music they engaged with on farms along the route.

Yes, I was the first rider in that day. But I had no stories. I didn’t meet any of the town locals. No food and beer stops. No memories other than spinning for 80 miles past thousands of acres of corn and soybeans in northwest Iowa, sipping my electrolytes and munching on energy bars, which is the standard approach for riding centuries and half-centuries (100 mile and 50 mile bike events). But as I soon learned on day one, Ragbrai is not the standard ride. At all.

I’d heard about Ragbrai for years but Iowa was a long way from my home on the West Coast to schedule a week long bike ride in the Midwest. Then I met an Iowa native in Mexico on a tequila tour who’d ridden the Ragbrai numerous times. We talked about biking. After a week of sampling tequilas, hanging out together, he determined that I might be a good candidate to ride with their crew - Team Bubba Clyde - of Iowa.

The Team Bubba Clyde Bus - 2014

I had no idea what I was in for.

Ragbrai would redefine the very essence of long distance bike rallies. For one thing, on day two, I joined a few Bubba riders for a beer at 10am. That calibrated a more moderate pace for the rest the day. I was relaxed, open to curiosity, spontaneous conversations, and roadside attractions. As my pace slowed, the stories began to unfold.

I met local people in the towns. A woman that raised dachshunds. I showed her a picture of our dachshund. I had apple pie in an Amish community. The pies were delivered by horse drawn carts. I sat with farmers on their lawns along the country highways and talked about farming. They liked that I’d spent summers on my grandparents farm in the Sacramento Valley and had toured the John Deere tractor plant in Waterloo, Iowa. I got to know the espresso cart owner from Iowa City that followed the Ragbrai across Iowa. He was always my first stop every morning, before the microbrew tents.

I also got to know Team Bubba Clyde since I was on their bus and we camped together every night. We would drift in and out of riding together as the hundreds of miles unfolded. About half of the Bubbas were from towns around central Iowa, a few had been riding the Ragbrai for more than 35 years and had established a core team that was pure culture. Some of their kids were riding with them now.

News reporters sometimes sought them out to get their views on the current ride. They knew the organizers. The other half of the riders on the Bubba Bus were a scattering of regular long-time friends who frequently joined the ride. Some had Bubba jerseys. And then a few like me who were invited to join the team as a guest rider. I rode with the Bubba Clyde Team in 2014 and 2018.

Another 2014 guest rider was a woman police officer from Iowa City. In 2018, she brought her canine into Iowa City to meet the group. She didn’t ride that year. Her German Shepard ran to my tent (among 15 tents) and urinated on it. She was mortified. In reciprocation she gifted me an Iowa City K-9 Police T-shirt, the envy of every rider on the 2018 team.

And then you encounter the unexpected, like riding along and discovering the Surf Ballroom in Clear Lake, Iowa, where the great music legends played through decades. Thousands of concerts have occurred there since 1933. Country legends, jazz greats, blues kings, and rock and roll stars all took the stage there. The biggest names. It was the last concert that Buddy Holly played, as his plane with Ritchie Valens and the Big Bopper went down on take off after a concert, on what became known as “The day the music died.”

Ragbrai buses are moving landmarks in the event.

There’s at least a couple hundred buses all fixed up, some are more modern, each one with a theme and its own history of riders and groups. Some are corporate and others are tight groups of longtime friends who love to bike and explore the towns of Iowa. The Bubba Clyde group is that. Their bus is an old school bus, privately maintained, white with red flames and a monkey in a helmet painted on the back door. It’s got a modern, semi-truck style wind spoiler on the roof to deflect highway winds from the 15 bikes mounted on top. A 100 gallon water tank for solar heated showers is perched up there as well. That shower is rejuvenating at the end of a day of riding. The inside of the bus is not fancy, but has bench seats down each side, 20 USB ports, and plenty of room for gear because we camp in tents every night.

The role of the bus is to get the team from Iowa City to the starting line on the Missouri and to drive ahead of the ride each day, carrying the camping gear, and to find a place in one of the seven towns that we’ll spend the night in over the course of the week. Most often the Bubbas have a friend, a relative or a friend of a relative, in all these small towns, who let us set up camp in their yard. Big Mike was our driver and camp site scout. He is the father of Little Mike who is a core Bubba rider.

One of the most compelling factors of Ragbrai is that the Iowa State Highway Patrol closes the state highways on the Ragbrai route. They close about a four to six hour window that moves with the mass of bikes across the state. Hour by hour. Day to day. If you linger too long toward the back, the troopers will politely urge you to catch up with the flow.

You are riding in a stream of thousands of bicycles on a two lane state highway with no vehicle traffic. You are always somewhere in the middle of the pack. You can see bikes miles ahead on the undulating landscapes, dotted with silos and wind towers. Town water towers become landmarks, almost like lighthouses along the coast. Suddenly a rider will call out, “Water tower!!” And you know the wide open country is about to funnel through another highly expectant small town. There will be food, drinks, entertainment, friendly and curious folks, and a place to rest. It may be the town where you stop for the night.

The mobile city disassembles in early morning hours as riders move on toward the next destination. You become a spec in the midst of a massive, traveling community, rolling between soybean and corn fields, thousands peddling toward the east, preceded by vans, semis and buses full of camping gear and outdoor kitchens.

Mobile grills, like the Pink Pork Chop Bus, pop up along the way each day, traveling with the community. Mr. Pork Chop has been grilling at Ragbrai for 40 years via three generations of family. Another roadside attraction, a group that crafts home made ice cream from fresh dairy, churned old-world style, with single piston engines, filling iced urns each day.

In the evening the rolling city slowly reassembles and implants itself in the next small town. When we gathered in Mason City in 2014, the largest town on that year’s ride at 28,000 people, Brett Michaels did a free concert in the center of the city. The Ragbrai swelled to more than 25,000 riders that weekend as a wave of two day riders joined the rolling community.

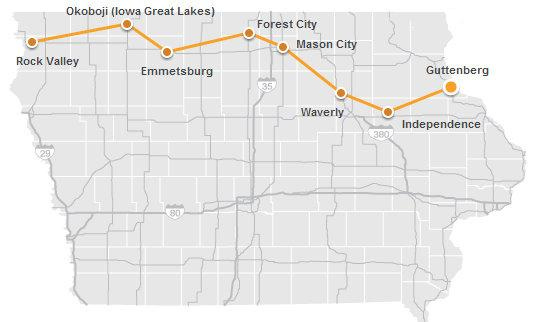

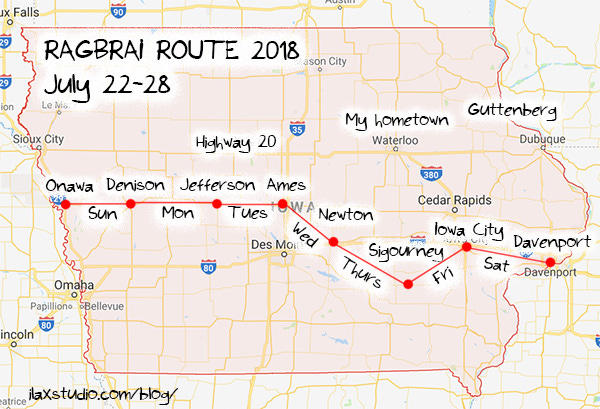

The Ragbrai charts a different route every year, visiting different towns (see maps at end). Sometimes the event will be routed through a town that got hit by a tornado or flood and is trying to recover. Ten to twenty thousand bikers spend a lot of money once they hit town, and, consume a lot of mobile bandwidth. Rural networks can get swamped until they no longer function when the Ragbrai wave descends on a small town.

The ride expands enormously once Ragbrai nears the center of the state. Riders pour in from Minneapolis, Des Moines, Chicago and other nearby cities to ride just a couple days. In 2023, the 50th anniversary of Ragbrai, 60,000 riders rode between Ames and Des Moines. The largest number of bikes ever gathered on a leg of the Ragbrai.

As the week progressed, I increasingly became one of the last riders to arrive in camp. My storylogue was building as I embraced the underlying nature of the ride. Though I was an outsider, a novice, I found that as you descend deeper into Ragbrai culture, you begin discovering a truly unique, American experience. France has the Tour de France. The US has Ragbrai, which is more like Burning Man on bicycles. Other states bordering Iowa have tried to replicate the cross-state bike phenomena because of the enormous success of Ragbrai, but they all failed to generate a lasting presence. Ragbrai was first held in 1973 and just celebrated its Golden Jubilee in 2023.

Team Bad Boy

One of the legends within the Ragbrai legend is Team Bad Boy, three riders from Colorado. I never met them, but saw them several times along the Ragbrai journey. They say if you are in the same town at the same time as Team Bad Boy, that you are in the heart of the event, though likely near the end of the pack, closing down towns, indulging in everything along the way. Team Bad Boy rides with a barbecue grill on one bike, a giant ice cooler on another, and a full-bar on the third bike. They ride from Colorado to Iowa to do the event, then ride back to Colorado. They are hard core.

You see scores of other remarkable sights and riders along the way. I met a woman from the Midwest who was pedaling an electric assist bike with an extended frame, that housed a 6-8 foot long wooden cabin where her three triplets sat in a row, each with a helmet, and a roof over the whole contraption. She was peddling the entire 450 miles, camping every night with her kids.

Then you might see people on skate boards and unicycles, going from the Missouri to the Mississippi. Lance Armstrong was cruising in the crowds in 2014. I think he was serving hamburgers at some point along the way, somebody said. Out in the middle of Iowa, I got passed by a guy on a bike made out of wooden 2x4’s and an axe head, which looked precarious. He worked in one of Trek’s facilities and took a bet about making a bike out of framing lumber and riding the Ragbrai. He said he kind of regretted his choice as the bike proved incredibly hard to ride over 400 miles.

At the End of the Ride

After you dip your tire into the Mississippi River, it’s a reverse scenario of the arrival at the Missouri River. You give your bike to the Iowa bike shop at the finish line that will take your bike apart, pack it in a road case or cardboard box, and ship it back to your home town. Just like they assembled the bike when you shipped it out. You grab your duffel bag of camping gear, jump on the Bubba Clyde bus and head back to Iowa City where you catch a flight to Denver, then to the West Coast.

Then you’re back home. You’re kind of thunderstruck at what just happened. Because you are not riding from dawn to dusk anymore, spinning the cranks everyday, even though you still feel like you’re in motion, covering hundreds of miles. Climbing the deceptive 12,000 vertical feet of rolling Iowa hills. Miles of Iowa countryside just keep playing through your brain. The crowds, the camaraderie, the small towns, the fields, the local people playing music, the open grills, the microbrews, the farms that host hundreds of bikers, letting people just wander around on their beautiful grounds.

I filmed a short music session that took place on one of the farms near Davenport on the Mississippi River in 2018. It summed up the ride in so many ways. Bicycle travelers were wandering around on this farm property while locals played music and served food. It was an incredibly welcoming, unassuming environment. A beautiful moment.

I’m still entertaining hopes of doing a 3rd Ragbrai one of these years!!!

jhg - 2018