Jailhouse Camping in Eastern Canada

With the tail end of a hurricane bearing down on Nova Scotia, my motorcycle and small tent offered scant protection from the wild elements so I asked the local jailor in Sydney if I could get a cell.

M2 - #2 of 4 stories in 1971, describing certain events on a 12,000 mile motorcycle journey across North America, including the Trans-Canada Highway, from Victoria to Newfoundland.

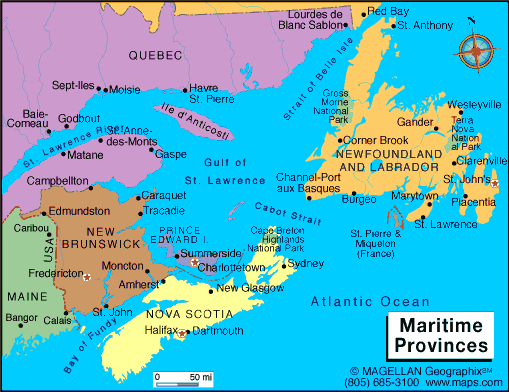

In August 1971, the remnants of Hurricane Beth swept up the Atlantic Coast and into Nova Scotia, dropping almost a foot of rain in the maritime province. I was riding my motorcycle across the 5,000 mile Trans-Canadian National Highway at the time - from Victoria, British Columbia to St. Johns, Newfoundland - and just happened to be in Nova Scotia when the storm came on shore. The winds were ferocious and the rain daunting. I didn’t have foul-weather gear and was short on money.

Jail One

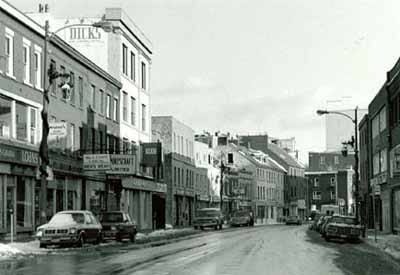

I think the notion of requesting a cell in Sydney, Nova Scotia’s old downtown jailhouse came to me because I’d spent three nights in Quebec City’s La Prison des Plaines d'Abraham the week before, sleeping behind bars in the giant, old stone prison structure that loomed over The Plains of Abraham. I hadn’t been incarcerated though. The cell door was unlocked and I was free to come and go and visit the sights of Quebec City. The prison was being used as a youth hostel during that time. But it left a strong impression. I’d never been in a prison before.

Jail Two

When I walked into the downtown Sydney precinct and asked the desk sergeant if he had an empty cell that I could spend the night in, he looked at me as if I was an idiot.

“No, you can’t sleep in the jail. Get outa here,” he said, though slightly amused.

I saw my opening.

“My tent’s no good,” I told him, making my case. It was pouring rain outside. “I’m supposed to catch the ferry to Newfoundland in the morning, to Port aux Basques. I don’t have much money. I’m traveling the Trans-Canadian Highway on my motorcycle.”

He’d guessed that I was an American shortly into the conversation. And that I wasn’t going to be a problem. The long motorcycle trip caught his attention.

“Just a minute,” he said, giving me a second glance. He walked into the jail cell area and came back. “Okay, you got a cell. But if we need it tonight, you have to get out.”

I was relieved. I parked my motorcycle at the police department’s door and brought in my travel gear. The dingy little jail cell felt like a fine hotel. They left the cell door open. There was even a rest room down the hallway. I laid back and read my book until the place quieted down and I went to sleep. I could hear the winds whipping and rain falling steadily outside in the night. I felt very fortunate.

A drunk woke me up in the morning at first light. He’d been in jail and was now wandering around the cell block. He thought I was in jail for some reason and wanted to know what I’d done. He lost interest when I said I was just spending the night out of the rain. I checked out of the jail and rode down to the Sydney Ferry dock. The rains had stopped but it was still very windy. The bay was covered in wide caps.

The ferry was delayed by four hours due to the storm. When the ship was finally ready to go, they lashed my motorcycle to the steel frames of the ferry hull. They chained down the automobiles. They said it was going to be a rough crossing to Newfoundland. A group of moose hunters down below decks stood at their vehicles drinking whisky. One offered me a drink. I politely declined. Drinking alcohol in rough seas would be a bad combination.

Everybody on the ferry was jubilant, and some drunk, when we finally pushed off the dock and headed north, out of Sydney Harbor. We were four hours late. The sea was fairly smooth for the first hour or two until the ship cleared the northern end of Cape Breton Island, which lay to the west. It had completely shielded the ferry from the open waters. Once passed Cape Breton Highlands National Park, everything changed. We picked up enormous, wind-driven swells rolling through the Gulf of St. Lawrence. The ship took the swells on its port beam and was rolling in 20 to 30 degree swings all the way to Newfoundland - a six to eight hour crossing.

I went down into the ship one time to use the marine head, but was disgusted at the mess. So many people were sea sick. They were lying on benches, some motionless. The bathrooms were a horror scene. People had puked on the floors and in the hallways. I went down to check my motorcycle. It was secured firmly to hull beams. The moose hunters were nowhere in sight. The party was over. I stayed topside the rest the trip, out in the fresh sea air, though the rolling was more significant on the topside deck. But in my mind, better than the nightmare below.

Once on The Rock (as Newfoundland is called), I began my ride, spending an evening with a local family I met at Cornerbrook, a small sea town along the way. I pitched my tent in their yard. Newfoundland was a nice place. Newfoundlanders were some of the most hospitable people that I’d ever met in my travels. It was easy to strike up a conversation. They seemed genuinely curious and approachable. Having a foreign license plate on a motorcycle with travel gear drew their attention.

Jail Three

Two nights later, I got hit with more winds and rain near Gander, the historic airport that served as a refueling stop for decades of flights between Europe and North America, including WW2. I went to the district RCMP (Royal Canadian Mounted Police) office and asked for a cell for the night. This was starting to be the way to go. I felt comfortable asking.

The RCMP desk officer looked at me, listened to my story, then agreed that I could have a cell. They had room.

“Empty your pockets on the desk,” he ordered.

Empty my pockets?? That hadn’t happened in Sydney. I was caught off guard. I had a marijuana joint in my pocket in a plastic bag. I had no idea they were going to ask me to empty my pockets. A Canadian guy had given me the joint at the Quebec prison.

“Okay”, I said tenuously. The RCMP were more rigorous than the Sydney police. I took out all the items in my jean pockets, except the joint, and placed the articles on the desk. I hoped they wouldn’t search me since I was a volunteer prisoner. They didn’t.

I was ushered into a corner alcove cell in the jail that was removed from the central holding area where most of the jail cells looked into. At least I had privacy. The trustee that took me there locked me into the cell and left with the key. This wasn’t Sydney at all. Now I was a prisoner, except I would have free passage out in the morning.

During the night there was an altercation between the trustee and one of the prisoners in a cell that I couldn’t see. The inmate was belligerent, raving, throwing things. The trustee left. Minutes later a very large RCMP officer stormed into the compound heading straight for the loud mouthed inmate, who immediately started pleading, “I’m sorry. I’m sorry. I won’t do that again! I’m sorry!”

It was too late.

The RCMP officer had a straight jacket in his hands. I couldn’t see what actually happened because the cell was around the corner. But I could hear all the sounds. The inmate was frantically begging for the officer not to straight jacket him. The officer said nothing, but he obviously manhandled the complainer and bound him in a straight jacket. The inmate shut up for the entire night. I was out of there at sunrise.

Jail Four

Jail Four didn’t happen even though I tried. I’d ridden into St. Johns, Newfoundland in the afternoon and the weather remained blustery and gray. But I was a well studied jailhouse rat by now, at least in my mind. I walked into the the St. Johns police department and asked for a jail cell, like the police desk was a hotel front desk. Do you have anything with a view? I didn’t say that. But I laid out my story, which I was comfortable telling by now. The desk officer listened, but said, “No, we can’t give you a cell.”

“Really?” I wasn’t expecting rejection. Newfoundlanders were some of the nicest people I’d met so far in North America.

I stood there bewildered, planning my response. But the desk officer was also a motorcycle cop in St. Johns. He took a personal interest. He had a motorcycle.

“Show me your bike,” he said.

We walked outside the station and he inspected my metallic red and gold Honda 750 4-cylinder machine. He liked the Wixom faring and windshield that offered wind protection. The crash bars. The four, flared, chrome pipes up the tail. The high-rise back rest for gear. He asked me a lot of questions about my bike and the 5,000 mile ride across Canada. We had a nice dialogue going.

In the end, he still couldn’t justify giving me a cell in the St. Johns’ jail house. Instead, he made a phone call home to his wife, then returned and invited me to stay at their apartment in St. Johns while I was in the city. They had a guest room. I could leave my bike at the station or at their apartment garage.

I spent three days with them. It was an incredible visit to one of the farthest east cities in North America. My hosts were both wonderful people. I enjoyed home cooked meals, the warmth of their hospitality, and we discussed long-distance motorcycling. He and his wife were planning a trip by motorcycle one day and they both had a lot of questions for me. My experience had grown tremendously after the first 7,000 miles.

St. Johns was also my turnaround point on an ultimate 12,000 mile round-trip journey that would take me back through the Maritime Provinces, through New England, across the Midwest and into the Rockies. There would be many adventures mixed into that final push across the country.

Stay tuned for the chilling finale to that trip that occurred on a Wasatch mountain pass, after midnight, in a winter snow storm, when I crashed my motorcycle.

jhg - 1971